KISS MY SWORD

⚔

KISS MY SWORD ⚔

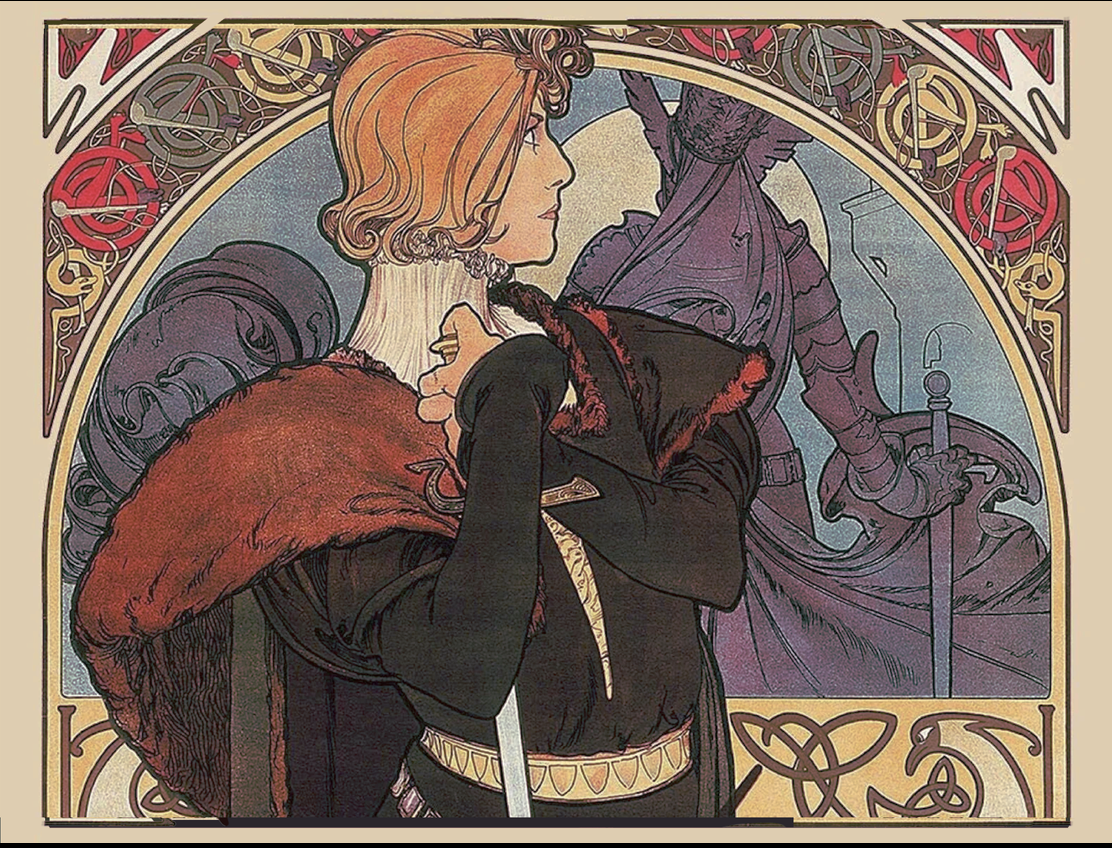

Kiss My Sword is an upcoming full-length opera about Julie d’Aubigny, who fought in the streets, stole and broke hearts, and commanded the stage of the Paris Opera in 17th century France. She famously cross-dressed, publicly kissed women, and defeated men in dramatic duels; gender roles and social rules were of no interest to her whatsoever. She is a figure that commanded attention then and she commands attention now. People love Julie – we love Julie. It’s very easy to love Julie. We wanted to think about why.

FAQ

⚔

FAQ ⚔

WHY JULIE d’AUBIGNY?

An openly queer, sword-fighting opera singer in 17th-century France: need we say more? (Of course, we want to!) We want to make a work about Julie, because despite her living centuries ago, she still feels contemporary to us. As we’ve shared this project, we’ve found that many – especially queer people – have heard parts of her story without necessarily knowing her name. Julie lived loud and fast, leaving behind a trail of stories and gossip that don’t quite line up. Her story resists neat facts. We’re interested in her because she’s slippery, complicated, and refuses to be pinned down. We want to think about queerness in history in all its messiness and contradictions, and Julie’s story lets us do that. We are making this work because we all find ourselves drawn to Julie, and it has taken us a while to articulate why.

HOW DID JULIE IDENTIFY?

It feels simplest to say we don’t know, because of course we don’t know! There are no primary sources that provide an answer, and no evidence for Julie’s own conception of self. We’ve used “queer” as a basic descriptor with the full understanding that this is a modern category based in a modern context, and she/her pronouns as that is what she would have used and what has been used for her in primary sources. How she actually felt about her gender and her resistance to conforming to gender roles, and how she would have defined herself as a person who openly had relationships with men and women both – these are questions up for debate. This is a work that is partially about this question, or specifically the desire to ask it. There are many interpretations possible, and we are not interested in closing off any of them, so have chosen to leave a definitive answer out of the text. That’s not to say we haven’t had many lively discussions about it!

WANT TO LEARN MORE ABOUT JULIE?

For a good non-fictional overview of what we know about Julie, there is an episode of Bad Gays podcast, which includes a source list. There’s also an episode of You’re Dead To Me. For written work, Kelly Gardiner’s Goddess (2014) is a novelisation of Julie’s life done as part of a PhD project – the book is a fictional biography, but some of Gardiner’s research can be found on her website. These are some relatively accessible ways of learning Julie’s history, getting an overview of what we do and do not know, and exploring the most (in)famous stories/myths about her.

The process of researching Julie was a long and winding one, and one which is barely over – we’re still finding new sources and perspectives on her even now. For a deeper dive into the primary sources and some links to interesting documents, see our blog post on the subject!

HOW ARE WE APPROACHING JULIE’S STORY?

When we began to research Julie, we were intrigued by the combination of very sparse primary historical sources combined with a multitude of stories, rumour and gossip across historical eras. We’re interested in the ways people have talked about Julie, from the 17th century to now, and how she exists more in legend than history. Kiss My Sword focuses on the fallibility of truth around Julie – on the sometimes contradictory stories – and asks the question of why we still find ourselves drawn to her. The music will experiment with the fluidity of time, and will honour Julie’s legacy as a baroque opera singer by occasionally engaging with baroque modes. We’re interested not only in telling Julie’s story, but engaging with the historical incongruities around her, and the impossibility of settling on just one ‘version’ of the story. Scenes of the opera sometimes feature multiple versions of a story playing out at the same time, or a questioning about the ‘truth’ of a scene.

ARE THERE OTHER CHARACTERS IN THE OPERA?

The many stories about Julie include a large cast of often extremely colourful characters. Many of these characters appear in the sidelines or referentially, but within the narrative of Kiss My Sword we have chosen to bear down on two characters who feel iconic to depictions of Julie. The first is the Comte d’Albert, a swordsman she defeated in a duel and who would go on to become one of the longest-running relationships in her life – one of the most recognisable tales about Julie. The second is the Marquise de Florensac, an independently wealthy noblewoman (and a formidable figure in her own right), and a person who Julie seemingly loved deeply. Like Julie herself, these are figures more of myth than fact at this point, and we have chosen to explore who they might have been (and in which ways they might have also been transgressive) in a more speculative way. After all, anyone who meant so much to Julie must have been fairly remarkable.

WHY DO WE FEEL THAT IT’S IMPORTANT TO BE MAKING QUEER OPERA?

We know that, for centuries, opera communities have been a space for LGBTQIA+ people, and traditional opera is full of queer potential and readings (see, for example, ‘pants’ roles in a lot of major operas). Despite this, most explicit queer representation in opera until recently was hidden with symbolism, communicating only to those who were open to queer interpretation. Opera that deals openly with queer themes and characters is still a relatively new phenomenon, and an exciting, growing space. As a team of queer-identifying artists, we want to offer a work to the operatic canon that unapologetically deals with queer lives and experiences and does so with complexity and nuance. We’re not just interested in visible queer performers or characters on stage (though this is important to us!) – we also want to think about queer approaches to form, and what these approaches might be able to contribute to the opera space, which we see as full of queer potential.

WANT MORE OF OUR WORK?

Check out some of our past collaborations:

Meta Cohen (composer), Evan Bryson (librettist) and Coady Green (pianist/producer):

Delphi Songs, a song cycle about prophecies, endings and the last Oracle of Delphi (song cycle for soprano, piano and two singing bowls / version for soprano, harp, prepared piano and two singing bowls) | MORE INFO | LISTEN

Meta Cohen (composer) and Evan Bryson (librettist):

Caedo, a choral work about ideological violence in the Crusades and beyond (winner of third prize in the Leonardo da Vinci International Composers Competition in Florence, Italy, 2023) | MORE INFO | LISTEN

Meta Cohen (composer) and Alyson Campbell (director/dramaturg):

promiscuous/cities, a symphony of a single night in San Francisco (theatre show, presented as part of the British Council’s UK/Australia Season in London) | MORE INFO

DFLTLX, or Doctor Faustus Lights The Lights, Gertrude Stein’s eco-feminist take on the Faust legend (theatre show) | MORE INFO

HOMO FOMO (upcoming), a show about the fear of dancing, the pursuit of queer joy and being a Bad Queer (theatre show) | MORE INFO

Meta Cohen (composer) and Coady Green (pianist/producer):